This is the second of a short series of blogs covering my talk from ResearchED Birmingham, from the 2nd of March, 2019. Part 1 covered the value of teacher experience.

As we’ve seen in Part 1, teachers generally become more effective over time as they accumulate experience. This increase in effectiveness is seen in both academic and non-academic outcomes as well as spilling over into the effectiveness of colleagues.

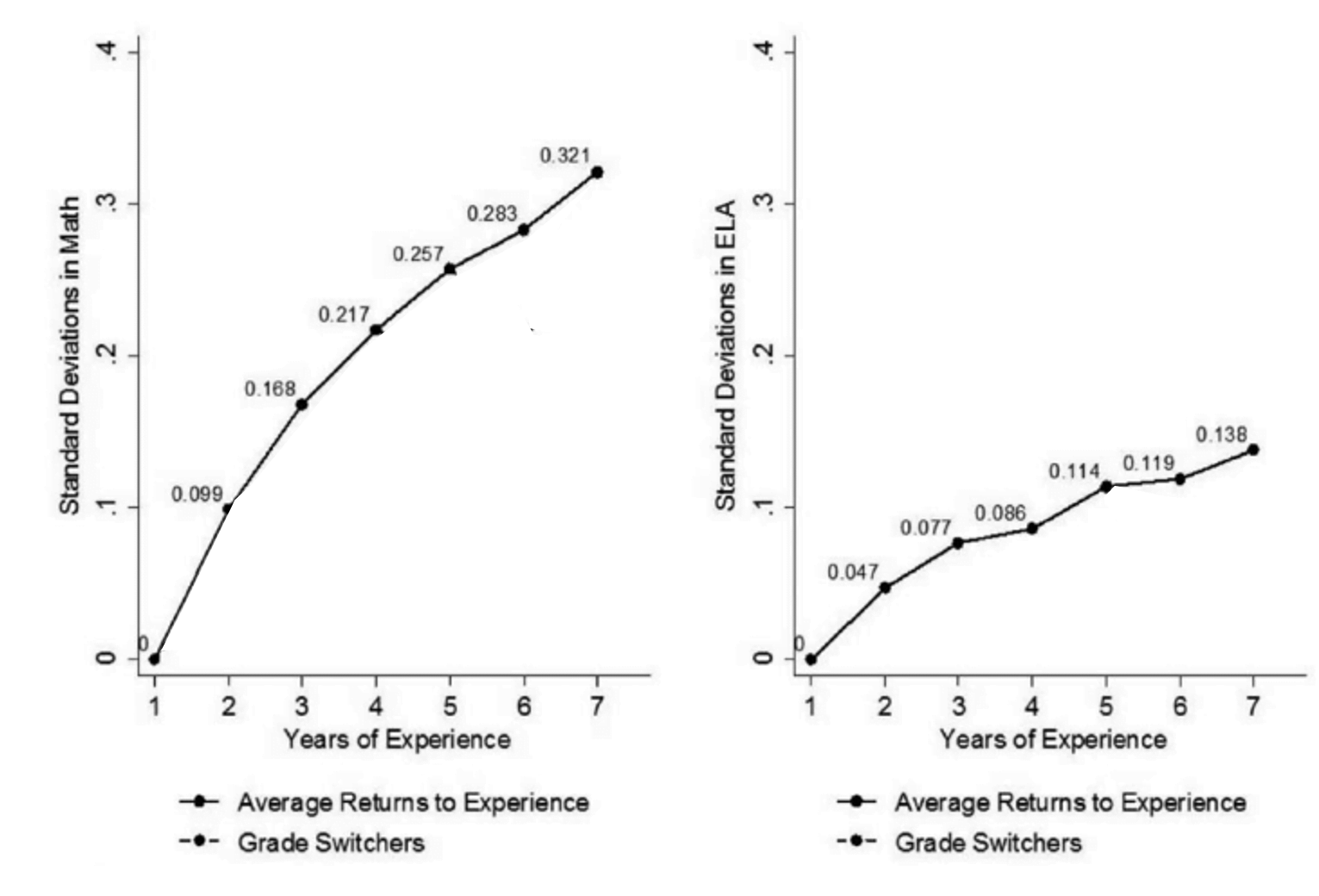

The question, therefore, is whether teachers become generically more effective or whether the particular year group and subject matter are important. Blazar (2015) took data from a wide range of elementary (primary) schools in California, from 2002 to 2012, and found that, on average, teachers became more effective over time in improve mathematics and English results:

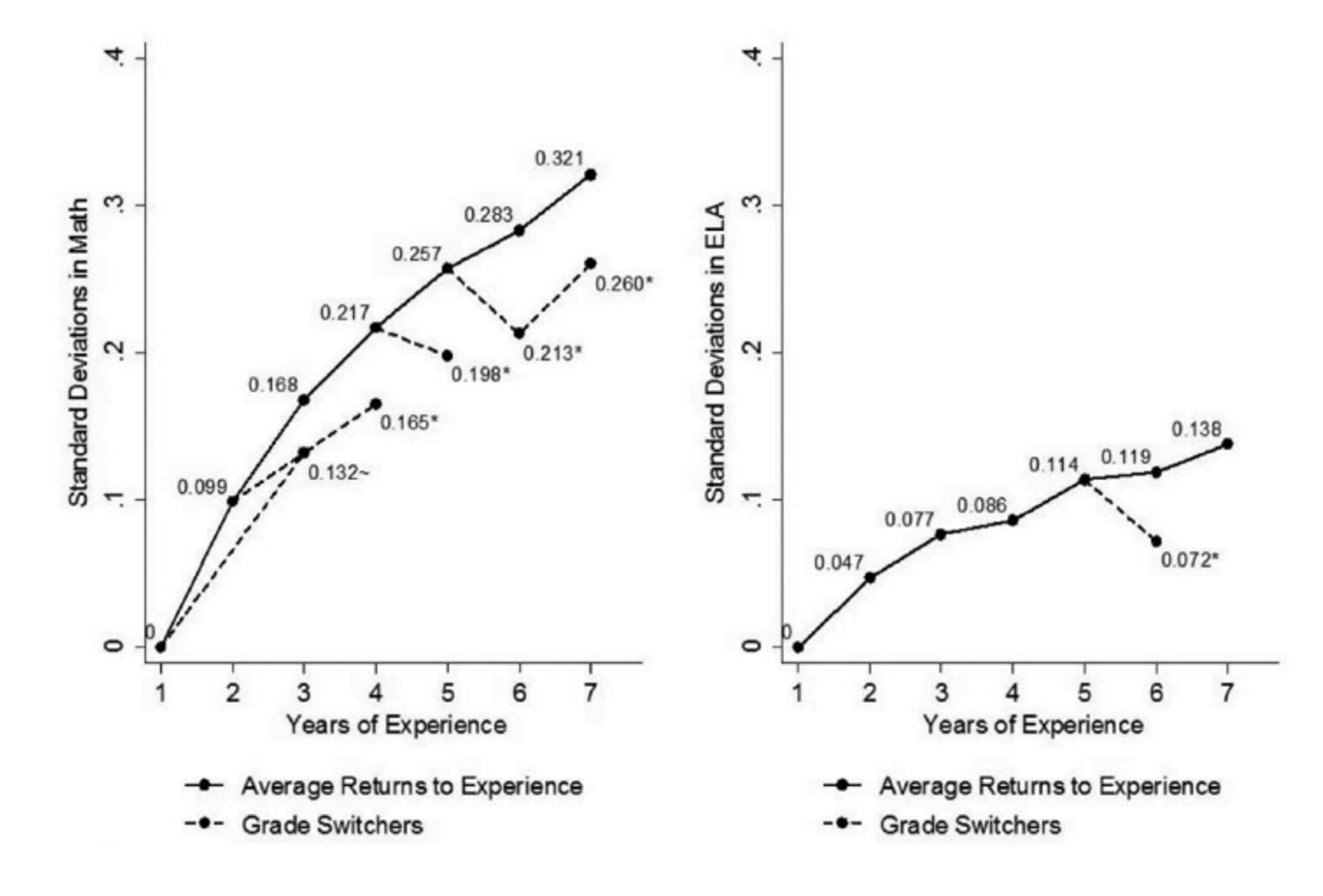

They then looked at the effectiveness of those teachers who had switched year-group (grade):

In all cases, this had a detrimental impact on the teacher’s effectiveness. In the case of teachers in the first couple of years of teaching, they improved more slowly, whereas for teachers who were more experienced they actually dropped in effectiveness. In one case, teachers switching year (grade) in the 5th year, there was sufficient data in mathematics outcomes to see that they dropped effectiveness after the switch and then started improving again the following year.

It is notable that fewer findings in English results were statistically significant – i.e. there was less evidence of impact of switching year-group (grade) on English results that there was in mathematics.

This finding is fascinating. It suggests that teachers can accumulate experience and effectiveness more rapidly if the content that they teach is held stable.

In a further interesting finding, Blazar found that the decrease in effectiveness was much smaller when teachers switched to adjacent year-groups (e.g. Year 4 to Year 5 or Year 3) than when they switched to non-adjacent year-groups (e.g. Year 4 to Year 6 or Year 2).

Blazar found that in less effective schools, teachers switched year-group (grade) more frequently and the least-effective teachers were the most likely to switch – a particularly vicious circle in which the most struggling schools and teachers are allocated in a way in which they are least likely to improve. Brummet et al (2015) also found that teachers were most likely to switch in schools in more disadvantaged areas and the teachers who were most likely to switch were the least experienced.

The findings above were all from elementary/primary schools and looked at switching within the school.

Atteberry et al (2017) looked at data from New York schools between 1999 and 2010. In their study they looked at elementary, middle and high school levels (i.e. all the way from primary through to secondary) and not only explored within-school switching, but also looked at between-school switching. They also explore the impact on student achievement of being allocated to a teacher who has been stably allocated, who has switched year-group/grade, has switched school or is new to the profession. The findings are fascinating.

- The most negative impact on student achievement is being assigned to a teacher who is new to the profession, followed by being assigned to a teacher who is new to the school, with the least negative impact (but still negative) of being assigned to a teacher who has switched year/grade.

- However, students are four times more likely to be assigned to a teacher who has ‘churned’ (i.e. changed year-group or changed school) than being assigned to a new teacher, so the impact of churn is more significant overall. “…the average student only encounters one brand new teacher between Grades 3 through 8, but four or five churning teachers in the same time frame.“

- There is also evidence that minority and underprivileged students are more likely to be assigned to ‘churning’ teachers. “we find some evidence that some schools experience more of this churn than others, and one might be concerned that schools serving disadvantaged populations of students are also the schools most likely to have instability in their teacher assignments. Our analysis also suggests that even within the same schools, historically underserved student groups may be more likely to be assigned to churning teachers

than their more privileged counterparts: While the average student has about a 24% chance of

being assigned to a churning teacher in any given year, a White, male student who is not FRPL eligible, is not an ELL student, and has not been suspended only has an 18% chance of being assigned to a churning teacher“

Grissom et al (2017) explored ‘churn’ in elementary (primary) in more detail and found that:

- second graders assigned to a teacher from another grade experienced the equivalent of

about 42 to 50 days less learning (that’s more than two months!) compared with students who were taught by an

experienced second grade teacher. When those students moved onto third grade, they were still losing about

22 days of learning. - school leaders were most likely to move their best teachers to grades/years with the highest stakes tests and to keep them there, meaning that learning all the way up to key years was less effective overall and ultimately caused difficulties in the high stakes tests.

Finally, Hill and Jone (2018) looked at the benefits for students where teachers remained assigned to the same group of students, moving up with them over the first few years of elementary/primary school. They observed “small but significant test score gains for students assigned to the same teacher for a second time” and found that “effects are largest for minorities, and there is some evidence that gains are most evident for students with generally less effective teachers”. Moreover, they found that “suggestive evidence of spillover benefits: students assigned to classes in which a large share of classmates are in repeat student-teacher matches experience gains even if not previously assigned to that teacher themselves. This suggests that effects at least partly operate through improvements in the general classroom learning environment“.

A review of all of the literature of this area by the Learning Policy Institute (2016) suggests that, overall, we should be encouraging policy-makers and system leaders to: “[i]ncrease stability in teacher job assignments. Research shows that teachers who have repeated experience teaching the same grade level or subject area improve more rapidly than those whose experience is in another grade level or subject. Of course, many factors

influence job assignment decisions, including teachers’ desires for professional growth and new challenges as well as principals’ needs for flexibility in management. School leaders, however, should be educated about the increased benefits of specific teaching experience and consider this in their decisions about teaching assignments.”

My take on all of this is that stability matters when it comes to improving teacher effectiveness.

We’ve seen benefits in terms of student attainment and teacher retention, while also finding that the least advantaged students and schools are often the most likely to experience the largest amount of teacher churn. In addition, we see that high-stakes accountability encourages school leaders to move the most effective teachers into the exam year groups which would appear to simply store up problems for later.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks